Life Line

The new art student walks into the college studio and is confronted with a naked person. Here is nude person standing in the middle of the room, staring out the window and surrounded by about a dozen easels, occupied by some familiar people who are drawing intently.

“Draw what you see,” says the tutor intermittently, “not what you think you see.”

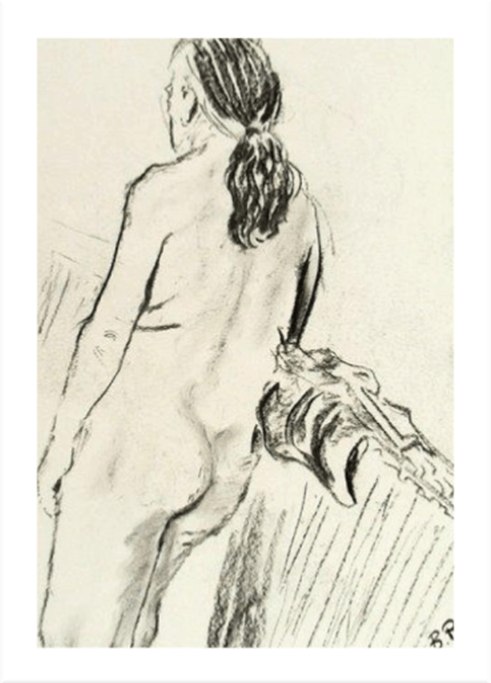

So begins the learning process: the embarrassment of producing on paper something akin to a newt or a gorilla soon outweighs the shock of coping with a silent naked stranger in your close proximity. “Look more than you draw,” says the leader, “Just keep your arm moving, search for the right line. No rubbing out! Erasers not allowed.”

Whattt? No eraser?

It has been said that life drawing is to the artist as practicing the scales is to the singer, and I absolutely agree. After a few years of frequent life drawing practice you can get reasonably proficient and create a drawing that looks like a living person. But have a month or more break from it and once again you’re drawing monsters or wooden manikins: you’re ‘rusty’.

You can’t help it, you need to keep at it to stop the rust setting in. And banishing your novelty rubber or even the lovely new soft one you bought especially, is a really good idea. You can always use a putty rubber at the end to tidy up the unwanted smudges from your charcoal or very soft pencil marks.

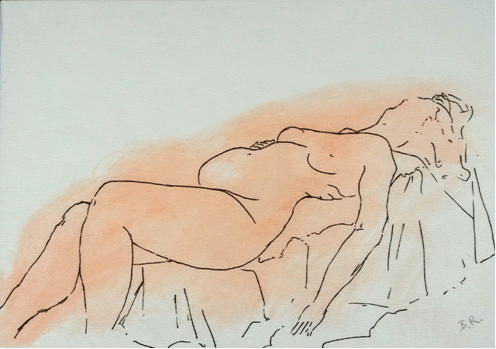

But why naked? Not because it’s harder. Models, however excellent at keeping still, do move slightly over the course of a ten or twenty minute pose. It’s up to the artist to accommodate the movement, not to draw a static figure that might as well be a copy of a photo but to capture the life of the breathing, twitching, wriggling-a-little-to-keep-the-blood-flowing model, who’s doing this job because the money’s helpful or because he or she likes to meet artists.

Why is it so important for the artist to practice life drawing? Because “Drawing is the true test of art,” said J.A.D Ingres (1780 – 1867), the neoclassical romantic regarded as one of the main precursors to modern art.

Life drawing makes you understand shape and depth, light and shadow, to help you create paintings that seem alive and full of character – better than any photograph. Learn, for example, how to draw a foreshortened arm without it looking like a birth defect. The same skill is needed for drawing a fallen log in a landscape and many other visual effects.

The Angel of the North, the massive sculpture overlooking Gateshead, might look stiff and ‘wooden’ at first sight; but its shape is accurate and couldn’t have been created without thorough and continuous study of the human form. See other examples like ‘Horizon Field’ and ‘Iron: Man’: there are many. The sculptor, Antony Gormley’s website says his work has developed ‘through a critical engagement with both his own body and those of others …’

Across 50 or so years I have attended life drawing sessions whenever possible because I love it and it doesn’t take long to get out of practice. Every artist knows that feeling of being ‘rusty’ and hoping that a few hours’ work in front of a live model will restore their talent, their confidence and inspiration.

In my studio I have a plan-chest that’s crammed full of drawings, some beautiful, some developed into paintings; and some life studies with big heads or tiny feet, disjointed arms or one leg longer than the other. All of them are a valuable part of the process: a fraction of my cannon of work and all of it shows who I am as an artist. I keep the good and the bad because it’s encouraging to see the improvements. When I’m well practised I can make an accurate line drawing with a permanent ink pen in just ten minutes.

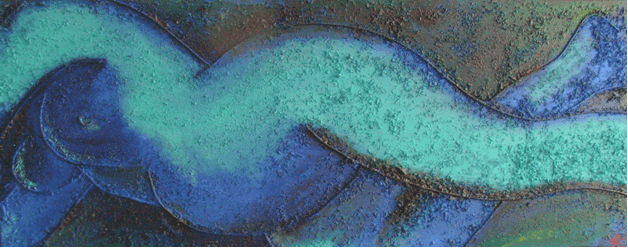

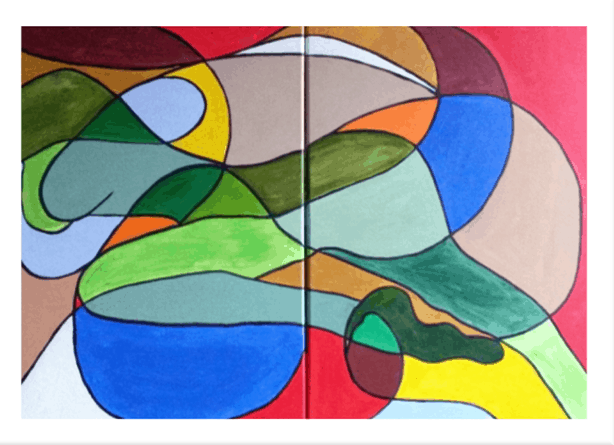

When I’m inspired to paint a figure in any situation or indeed an abstract, I can refer to my drawings for an interesting pose or characteristic and create something freehand that becomes an iconic picture.

Without life drawing I would not be able to sensitively draw three dimensional trees or a well-worn pair of boots. It’s all about volume and proportion, as well as distance and perspective.

Rodin was a prolific draughtsman, producing some 10,000 drawings; over 7,000 of which are now in the Musée Rodin, Paris. As the sculptor himself said at the end of his life, “It’s very simple. My drawings are the key to my work.” (Benjamin, 1910).

It is with the confidence of many years’ life drawing that I can invent abstracted figure work as pure self-expression; and focus on the shapes that are right for the composition without being concerned about body parts that are of no consequence to the painting I want to produce.

After initial instruction in life drawing classes you may soon find that all you need is the chance to draw from a live model, with no instruction at all. It’s many years since I began drawing nude models and for most of them I’ve been happy to get on and do it without a tutor, because even though I get limbs or heads out of proportion sometimes, I’ve learned to be objective and I know as soon as I stand back, what’s wrong with the thing I’ve produced.

The rigorous artist cultivates a relationship with the materials and tools to know how to get the best out of them: achieving believable gesture, mass, line, structure, shape, volume and colour. Life drawing cultivates good observation, decision making, understanding of negative shapes and above all, perhaps, simplicity. For when it comes to the finished piece we should remember the power of the viewer’s imagination: the human mind completes an image.

“In art, one does not aim for simplicity; one achieves it unintentionally as one gets closer to the real meaning of things.” ~ Constantine Brancusi

© Copyright Bernie Ross 2017

Bern Ross runs the online store www.modernartbypost.com where some of her life studies are for sale along with seascapes, landscapes and abstracts. Her writing name is Bernie Ross (short for Bernadette) and she spent many years as a writer, tutor and publisher. She has always been, and is still, a prolific creator. As another way to ensure her creativity improves people’s lives she runs monthly writing competitions offering feedback for each entry, and the winner’s chosen painting is their prize.

That was really interesting, cheers 🙂

I’m glad you found it interesting Chris, thanks for stopping by!